By Joseph Chamie

NEW YORK, Mar 2 2021 (IPS) – The demographic impact of the coronavirus one year after being declared a pandemic on 11 March 2020 has been enormous. The picture that emerges is one of significant consequences on the levels and trends of the key components of demographic change: mortality, fertility and migration. In terms of mortality, the reported number of Covid-19 deaths worldwide is approaching 3 million, with nearly 120 million coronavirus cases. However, it is widely recognized that the reported global number of Covid-19 deaths is an underestimate. In the U.S., for example, Covid-19 deaths are estimated to be undercounted by 36 percent.

Applying the U.S. undercount figure to the world yields an adjusted total number of Covid-19 deaths of approximately 4 million. If the adjusted number of Covid-19 deaths were excess deaths, the number of deaths worldwide turns out to be about 7 percent higher than the expected normal annual number.

In the U.S., the country with the largest number of Covid-19 deaths, it is estimated that fatalities nationwide were 20 percent higher than normal, amounting to a half million excess deaths, from 15 March 2020 to 30 January 2021. Estimated higher proportions of excess deaths, approximately 37 percent, have also been reported in England and Wales and Spain.

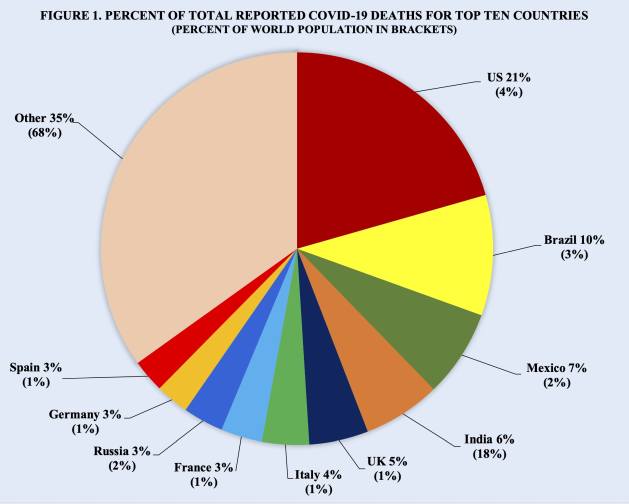

In terms of the distribution of Covid-19 deaths, the top ten countries, whose combined populations amount to one-third of the world’s population, account for two-thirds of all reported deaths (Figure 1). The U.S., with 4 percent of the world’s population, is in the lead position with 21 percent of all Covid-19 deaths, or more than half a million fatalities. Following the U.S. are Brazil, Mexico and India with 10, 7 and 6 percent, respectively, which together amount to approximately the same number of deaths as the U.S.

Covid-19 death rates provide additional insight into the deadly impact of the pandemic. The ten highest Covid-19 death rates per 1 million population are observed in more developed countries and except for the United States are all in Europe (Figure 2).

The diversity of Covid-19 death rates among countries is particularly noteworthy. China and India, together representing 36 percent of the world’s population, have Covid-19 death rates that are small fractions of the rates observed in the top ten countries. Also, the U.S. Covid-19 death rate of nearly 1,600 per 1 million far exceeds the rates of Australia (35), Canada (579), Germany (842), Israel (625) and Japan (62).

For most countries with available data, men have higher Covid-19 case fatality rates than women. However, in several countries, such as India, Nepal and Vietnam, the case fatality rates of women are higher than those of men. In addition to biological factors, social factors may also be playing an important role in sex differences in Covid-19 death rates.

The risk of severe illness and death from Covid-19 increases with age, with the elderly being at the highest risk. In the United States, for example, about 80 percent of the deaths were to those aged 65 years and older. And among that older age group, Covid-19 was responsible for 14 percent of all reported deaths from all causes from 1 January 2020 to 13 February 2021. U.S. data also indicate that among those aged 75 years and an older one in twenty infected with Covid-19 dies.

Provisional data for several hard-hit countries are finding that the pandemic has resulted in significant declines in life expectancy at birth. Data for five provinces of Italy found declines of several years in life expectancy at birth, with males having greater declines than females. Those findings represent the largest decline in life expectancy in Italy after the 1918 influenza pandemic and the Second World War.

In the United States for the first half of 2020 life expectancy at birth declined by 1.2 years for males and 0.9 year for females. Significant differences in life expectancy decline were also observed among major U.S. socio-economic groups (Figure 3). The largest decline in life expectancy at birth was 3 years for non-Hispanic black males and the smallest decline was 0.7 year for non-Hispanic white females.

The coronavirus pandemic has also influenced fertility in many countries but in very different ways. Some developing countries, including India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Uganda, are reporting the beginnings of a baby boom, believed to be largely due to women being unable to access modern contraceptives.

In contrast, many other countries, including China, Italy, Germany, France, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States, are facing declines in births pointing to a baby bust. In China, for example, it is estimated that fewer babies were born in 2020 than in any year since 1961 when China experienced mass starvation.

Due to the disruptions, lockdowns and uncertainties caused by the pandemic, couples are increasingly deciding to postpone childbearing. And delayed childbearing typically leads to lower fertility. In the United States, for example, around 300,000 fewer births are expected in 2021.

Levels of sexual activity have also fallen. The largest declines in sexual activity are reported among those with young children and school-age children who are not attending schools but are at home.

In their attempts to stem the spread of the coronavirus, governments worldwide closed their borders, issued travel bans, and severely limited migration. Those steps have been largely ineffective in halting coronavirus’ spread across countries and regions.

However, as a result of those travel bans, restrictions and lockdowns, migration across international borders came to a virtual standstill. In a matter of several months, the world experienced the biggest and most rapid decline in global human mobility in modern times.

Many migrant workers were unable to travel in search of work and many headed back to their home countries. Due to the border closings and travel restrictions, however, some migrant workers were stranded abroad and unable to return to their home countries.

In addition to migrants, business travellers and tourists, the closing of borders significantly limited the entry and processing of refugees and asylum seekers. Despite the border restrictions, however, many men, women and children have continued to cross international borders unlawfully without being tested for Covid-19, leading to increased risks of coronavirus transmission in transit and destination countries.

By mid-2020 the United Nations Network on Migration and several human rights groups called on governments to suspend deportations and involuntary transfers. The deportations created health risks not only for the migrants but also for government officials, health workers and the public in host and origin countries. For example, by late April the government of Guatemala reported that nearly a fifth of their coronavirus cases were linked to deportees from the U.S.

The pandemic has also impacted internal migration. In many countries, both more developed and less developed, the coronavirus has caused a reverse migration from cities to less populated places and rural areas.

With higher effects of the coronavirus closely linked to high density urban living combined with prolonged urban lockdowns and related restrictions, people are reconsidering their decisions regarding the place of residence. In various developing countries, including India, Kenya, Peru and South Africa, many urban dwellers are returning to their rural villages.

One year after the pandemic was officially declared, the enormous demographic impact of the coronavirus is becoming increasingly evident as more data are compiled and analyzed. While increased mortality is perhaps the most striking demographic consequence, the coronavirus has also significantly impacted fertility and migration.

With the availability of vaccines, improved public health practices, changes in social behaviour and the prospects of achieving herd immunity, the demographic effects of the coronavirus appear to be slowly abating. The daily numbers of reported coronavirus cases and Covid-19 deaths are declining, migration levels and travel are gradually improving and people are becoming more hopeful about the near future.

Nevertheless, serious concerns about the pandemic lie ahead. One concern is the emergence of more contagious and possibly more lethal variants of the coronavirus. Variants of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus first detected in China have already been reported in Brazil, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States. If these variants begin to spread widely, another spike in cases and deaths may occur in the coming months.

Another concern involves the formidable challenges in ensuring global availability and access to Covid-19 vaccines, especially among low-income nations. While about 225 million doses of vaccines have been administered by the end of February, most of them have been in high-income countries.

And somewhat ironically, there is the concern of large numbers of people in various countries around the world choosing not to take the coronavirus vaccine. Based on more than a dozen country surveys it is estimated that approximately a fifth of people across the world would decline getting a Covid-19 vaccine. High proportions choosing not to be vaccinated threaten the goal of achieving herd immunity and raises the contentious issue of deciding on what activities the unvaccinated will not be allowed to do.

Given these and related concerns, the coronavirus may continue to have a significant demographic impact on the world’s population in the coming years. While numerous things about the coronavirus pandemic remain unclear, unresolved and puzzling, one thing appears certain for the second year of the pandemic: many more people will have Appointments in Samarra.

Joseph Chamie is a consulting demographer, a former director of the United Nations Population Division and author of numerous publications on population issues, including his recent book, “Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters“.