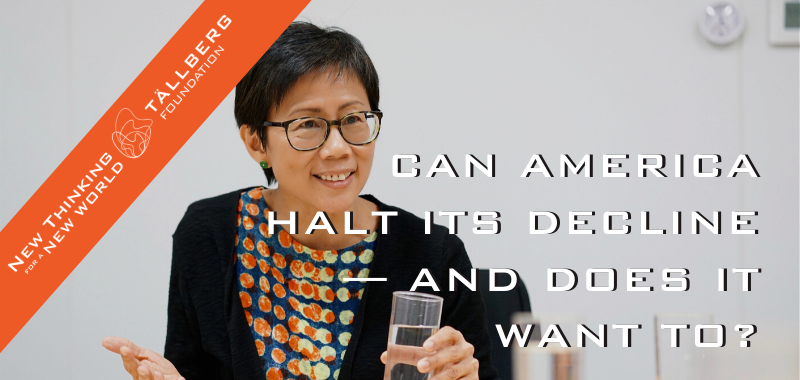

Alan Stoga

“We’re shocked, for example, that trains don’t work. We are shocked that the digital infrastructure is not good … America doesn’t not just invest in itself; Americans don’t invest in each other.” — Christine Loh

What’s wrong, America? What has turned the global superpower and self-defined moral leader into a nation whose president insists the country needs to be made “great again,” thereby admitting it isn’t? Can Americans have a frank conversation among themselves to chart new ways forward? Christine Loh is a Hong Kong-based environmentalist, academic, and former government official who has a long history observing, living in and thinking about the United States. Her recent conversation with Tällberg Foundation chairman Alan Stoga for the New Thinking for a New World podcast series delved into her deep concern that the country’s crisis goes well beyond a mishandled pandemic and a querulous presidential campaign.

“Foreigners coming to the U.S. don’t necessarily first see its politics,” she says. “For such a capable country, such a talented country, such a rich country, America has stopped investing in itself.” She recalls decades ago when her father returned to Hong Kong from his first trip to America, amazed at the country’s wealth and modernity, especially compared to the poverty in Asia. Today, it has reversed: The tattered infrastructure, poor schools, and weak governance are now in the United States. Making matters worse, many Americans seem blind to their own decline: “I think America also finds it hard to believe that they’re behind,” Loh says.

According to Loh, some observers in Asia have grown skeptical of the very foundations of the American story: “We even ask the question, ‘Is democracy the be all and the end all? Maybe we don’t want an American kind of democracy.’” Loh explains that this doesn’t necessarily lead to the conclusion that all democracy isn’t worthwhile. “It just means that perhaps … there is something about the American system that isn’t working, which results in the division and the polarization,” she says.

It is at this point where Loh’s two concerns merge. She says, “I think as you get deeper into it, you realize that yes, the politics is not spending money on these basic things”—like infrastructure and education—“and then you look at Asia and other parts of the world where [you] have less money, … but you plow your money back into your own people. This is a fundamental point for Asians in judging America.”

Can America stop this accelerating decline? Loh is unsure—but she is worried by the lack of a national conversation about all the challenges dragging down the country, and she is deeply unimpressed with the presidential campaign as it is unfolding. “We’re not hearing the kind of discussion one would usually associate with a presidential campaign,” she says. Loh admits that the U.S. probably can’t resolve its problems in one electoral cycle. Though if the country doesn’t quickly address them, then “I’m afraid other parts of the world will continue to develop, whereas America will not be able to solve its very basic problems.”

Nonetheless, she thinks that America’s recent, intense confrontation with its deeply ingrained white supremacy after the George Floyd killing has global import. “I wonder if this narrative actually can help the world,” Loh says, “because the world is mesmerized by what’s happening in America and is responding to it.” People have a chance to reconsider these past several hundred years of white Christianity claiming to be the way to civilize the world. “Today, we know that’s actually not what has happened.”

In a way, Loh points out, the United States—a former colony that became a world superpower—is watching an updated version of its own movie. As nations with different histories and perspectives like China and India rise in power, then white Christian imperialists may need to adapt their vision of how the world should work. Loh puts it this way: “How can everyone look at a much more diverse range of narrative and learn to respect each other’s differences?” As she explains, America may need to confront its history of racism, particularly with the black community, but “this also opens up a bigger discussion for America to cope with the non-white, non-Christian world.” Indeed, far more than one country across the globe could “use this opportunity to think about itself and where it wants to go.”

Loh thinks the United States will struggle to regain its self-appointed role as a global moral leader. Indeed, she wonders if the country “really wants to play that role anymore.” But she also doubts the world will continue to tolerate America wielding “human rights as a sword to achieve political purposes in other countries.” That game, she suspects, is over.

However, what is at issue is a fundamental debate over the nature of governance that is universal, yet particularly striking in the United States. How does a nation find the proper balance between individual rights (which, she says, Americans maximize) and collective responsibilities for the common good? “When I was young, I thought rights were all that mattered,” Loh says. “Now I think rights must be balanced with responsibilities.” She points to the very different response to the Covid pandemic in the United States compared to those in Asia, where governments and citizens quickly acquiesced to the communal solutions with which Americans still struggle. Especially masks: Asians cannot imagine how anyone could turn them into political symbols instead of barriers to spreading disease.

Loh suspects that solutions may not lie with leaders since most of them are consumed with politics rather than good governance. Perhaps real change can only come from the people themselves. “Maybe the people, rather than just leaving it with the government, should also talk about responsibilities,” Loh says. “We haven’t had that discussion now in the world for a very long time.”

– Tallberg Foundation