MAJURO, Mar 28 2019 (IPS) – Meretha Pierson has been a nurse for the past seven years, working in the government-run leprosy clinic in Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands. Her patients come in all ages, from different economic backgrounds and different professions. But, aside from their diagnosis, they all have something else in common: everyone wants to keep their illness a secret.

“Everyone requests me not to tell their neighbours. But women who are young, request me to not inform even their spouses. ‘Please don’t tell my husband,’ they say. Sometimes, such a request is really hard to keep,” Pierson tells IPS.

Unwanted labels

There is a reason why Pierson, one of the handful of trained health workers who can detect a case of leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, can’t always promise full confidentiality to her patients.

Marshall Islands is believed to have 50 to 80 new cases of leprosy every year – a number that is very big for a population of only 60,000.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), if more than 1 in every 10,000 people are affected by leprosy, then it should be considered as a disease that has not been eliminated.

Marshall Islands, as classified by the WHO, is therefore far from eliminating the disease.

But it is a classification that the government is eager to get rid of. In mid-2018, the government and the country’s Ministry of Health, ran a three-month long health screening campaign where over 27,000 citizens were tested for both leprosy and tuberculosis so that every affected person could receive treatment.

Concrete details on the number of leprosy cases are yet to be made public, but health workers like Pierson have already been instructed to keep a close eye on the patients who do not return to report on their health and who stop treatment in the middle of the course. And this is why it makes it really difficult to keep the promise of not alerting anyone to their illness as health workers are often compelled to seek out the patients.

Tracking these patients down and convincing them to restart their medication is both a necessity and a requirement that forms part of the government’s new campaign to curb the disease.

But as they do so, the requests for confidentiality becomes more frequent.

“They do not want us to go to their houses. So, we make phone calls, call them to a place outside of their homes and their neighbourhood and that’s where we do our counselling and advise them to return to the clinic for a check-up and continue the treatment. But it’s hard,” Pierson tells IPS.

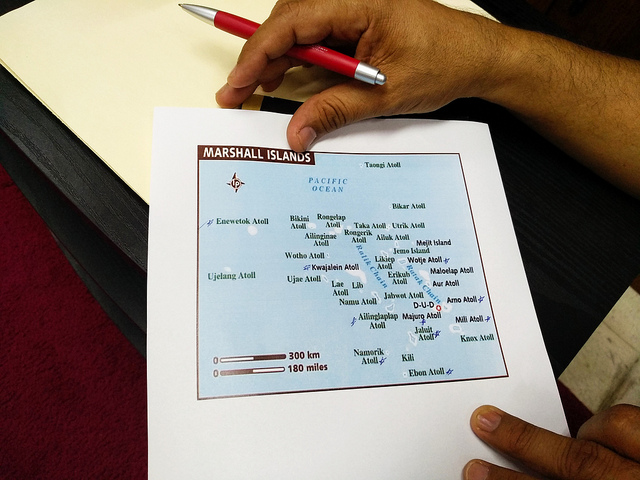

The leprosy hotspots in the Marshall Islands. Credit: Stella Paul/IPS

Discrimination towards the caregiver

However, it is not only patients who are stigmatised on this island nation. Health workers themselves often bear the brunt themselves in a society where over 80 percent of the population are of Christian faith. Pierson, a Mormon, says that she has often faced discrimination from her neighbours and relatives who have suspected her of having leprosy.

“They think because I work in a leprosy clinic, I am carrying the germ or the disease myself. Some even ask why I do not give up this job. I have to always tell them that I am a nurse and I do not have leprosy myself. Even in the church, I get those stares,” she says. Fortunately, her husband is supportive and has never asked her to leave her job.

The hotspots

There are around 30 atolls that comprise the Marshall Islands and about a quarter of them are known as the hotspots of leprosy, according to Dr. Ken Jetton, the main physician at the country’s Department of Public Health.

Jetton officially diagnoses and confirms leprosy cases after Pierson detects a possible case and refers the patient to him.

He tells IPS that few of these ‘hotspots’ include the atolls of Kwajalein, Ailinglaplap, Mili, Arno, Wotje and Ebon. During the recent mass health screening, about 47 new cases were reported from these places.

The data sheet is yet to be complied, but once this is done, a proper plan will be drawn up to treat each patient until they are cured, Jetton reveals. The medication, Multi Drug Therapy (MDT), an oral medicine, is given free of charge in 6 packs for children and 12 packs for adults.

Understanding the gaps in country’s leprosy elimination campaign is one of the reasons why a team from the Sasakawa Memorial Health Foundation (SMHF), led but its executive director Takahiro Nanri, as well as the world’s leading expert on leprosy, Dr. Arturo Cunanan, are travelling around the Marshall Islands and the Micronesia region. They have been meeting with senior government and health officials and leprosy experts and have visited clinics in Marshall Islands and the Federated State of Micronesia. Yohei Sasakawa, chair of the Nippon Foundation, the parent body for SMHF, is the WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination, and Japan’s Ambassador for the Human Rights of People Affected by leprosy. He will be touring the region in April to also assess the progress governments have made.

However, Pierson says that despite the screening and follow up activities, social stigma, especially towards the female leprosy patients might take longer than expected to fade away. This is because the island nation is still largely ignorant of the fact that leprosy as a curable disease, she explains.

Patience, therefore, is the key, she reminds. “We must be patient and also have empathy for those who hide their diseases from others. They are vulnerable and scared of losing their dignity and we need to understand this,” says the nurse.