Europe can remain a manufacturing hub if it ensures early adoption of game-changing technologies, engages with global supply chains and manages the green transition.

Manufacturing is dead, they said. But after four years, ten research reports, 47 case studies, an analysis of 27 policy instruments, countless seminars and debate, the Future of Manufacturing in Europe project is anticipating no funeral. Quite the contrary: the findingsfrom this innovative project place manufacturing at the heart of Europe and jobs to the fore.

At the behest of the European Commission, stemming from a proposal by the European Parliament, the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) has looked in detail at how manufacturing is changing on a global scale, how the industry will further evolve and what the impacts on Europe will be—everything from redefining tasks for meat packers in Sweden to the potential fallout of a trade war among the United States, the European Union and China.

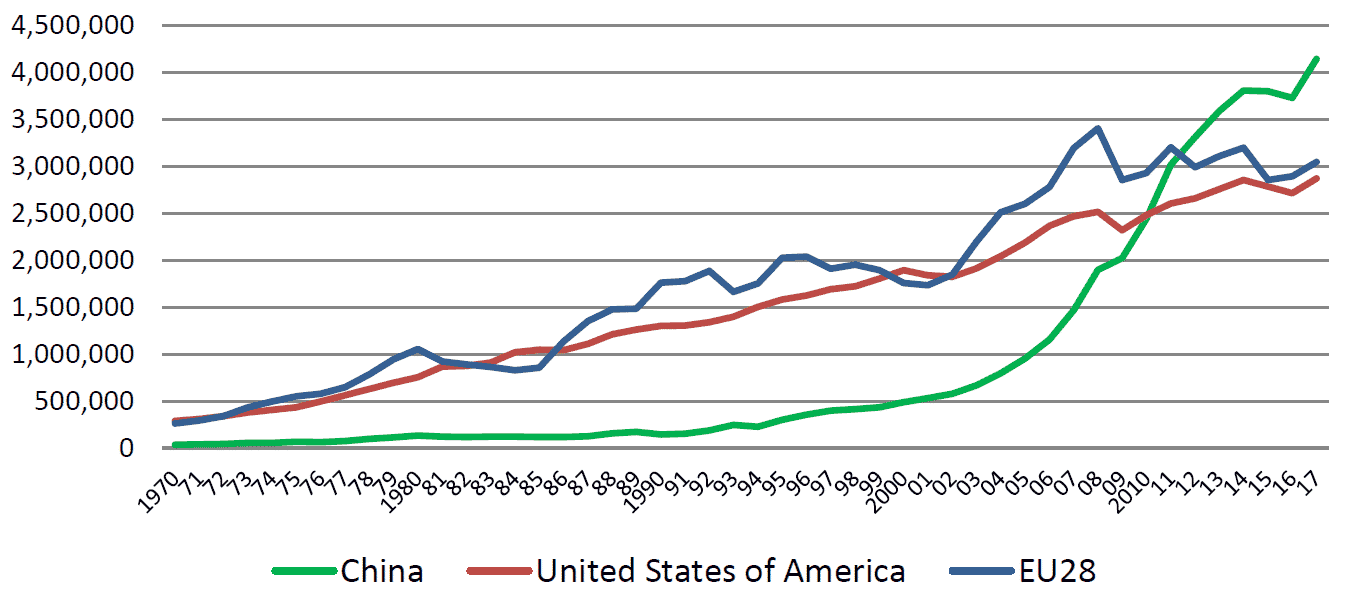

Value added in mining, manufacturing and utilities 1970-2017 (US dollars at current prices in millions)

Source: UN Conference on Trade and development

The research highlights the potential labour-market effects of automation and technological innovation. Overall, it finds that developments in technology and continued access to global markets can bring significant dividends for Europe—but only if it manages the transition.

For instance, the results show that taking the lead in the commercial adoption of emerging technologies will create more jobs and will give Europe a decisive competitive advantage over other global trading blocs, such as the US and China. More jobs will also be created if Europe actively engages in international production networks or global supply chains (rather than investing in further efforts at reshoring, which is unlikely to boost employment). And implementing the Paris climate agreement in full, will, in fact, ensure enhanced growth and employment opportunities for the EU.

What’s more, in general these jobs are likely to be ‘better’, requiring new and higher skills, alongside a reduction in the arduous jobs of the past. It is only the projected increase in global tariffs which looks likely to cause EU job loss in this context, according to these findings.

So, it would seem, far from the doom merchants’ estimates of huge and significant job loss as a result of automation and new technologies, this is good news. But what does it mean in practice?

Game-changing

Currently, the commercial application of the technologies studied is limited and mainly confined to highly productive firms. But, as the research shows, they can potentially have a game-changing impact and early adoption will give Europe a very clear competitive advantage. The realities of international competition make the adoption of productivity-enhancing technologies in manufacturing, and engagement in international production networks, an imperative.

And while there are still clear concerns about the impact of these new technologies on jobs and employment, they should be assuaged. Historical evidence shows that employment growth goes together with technological progress. The more the productivity gains go to consumers and workers, the more positive these effects are.

Indeed, the daily tasks of workers in manufacturing are already changing. The importance of physical activities is generally declining due to automation. With more intensive use of digitally controlled equipment, and the growing significance of quality standards, manual industrial workers will be conducting increasingly intellectual tasks.

So far, so good. But ensuring that workers are adequately prepared for the labour market and economic changes that are already under way will be fundamental for the growth of manufacturing industry and Europe’s broader economic success. Future workers, primarily young people, also need to have the most appropriate and relevant training, including via vocational education and apprenticeships, if ‘industry 4.0’ is really to be an economic, social and employment success.

Scenarios

Likewise, Europe must be agile and adaptable to the changing industrial and economic environment if it is to ensure its competitive advantage. The energy scenario set out in the research envisages a successful transition towards a low-carbon economy, as defined by the Paris accord, resulting in a 1.1 per cent growth in gross domestic product and a 0.5 per cent increase in employment in the EU by 2030, compared with a largely ‘business as usual’ baseline. But this implies a high-level commitment to effective management of this process—as these positive figures are largely down to the investment activity required to achieve such a transition—together with the impact of lower spending on the import of fossil fuels. (In the same scenario the US would initially experience a 3.4 per cent drop in GDP, and a 1.6 per cent decline in employment.)

Similarly, Europe will continue to face the economic protectionism which has been on the rise since 2008 but has increased significantly under the current US administration. The trade scenario presented in the research shows that the world’s largest economies would suffer economically from a further significant hike in trade tariffs. In the case of the EU, the bloc would experience a 1 per cent contraction in GDP, a 0.3 per cent lower rate of employment, and a 1.1 per cent decrease in imports by 2030, compared with a ‘no new tariffs’ default scenario. Despite some recent growth of trade in services, merchandise still comprises 70 per cent of global trade.

With consumer growth expected to be much faster in many parts of the world outside of Europe, the future of manufacturing, and so much of the material welfare enjoyed by people in Europe, is highly dependent upon globally competitive European manufacturing with access to these markets. The implications of a tariff war must therefore be carefully anticipated—only adaptation to economic and industrial change, rather than seeking to insulate Europe from it, will ultimately benefit manufacturing and bring more jobs.

The economic, skills, training and environmental challenges which this research has detailed will require a concerted approach from industry experts, national and regional public authorities, the social partners, academics and policy-makers. Political impetus and economic initiative will thus be at a premium if manufacturing is to remain alive and well in Europe.t

About Donald Storrie

Donald Storrie is chief researcher at Eurofound and leader of the Future of Manufacturing in Europe pilot project. He was previously director of the Centre of European Labour Market Studies in Sweden.