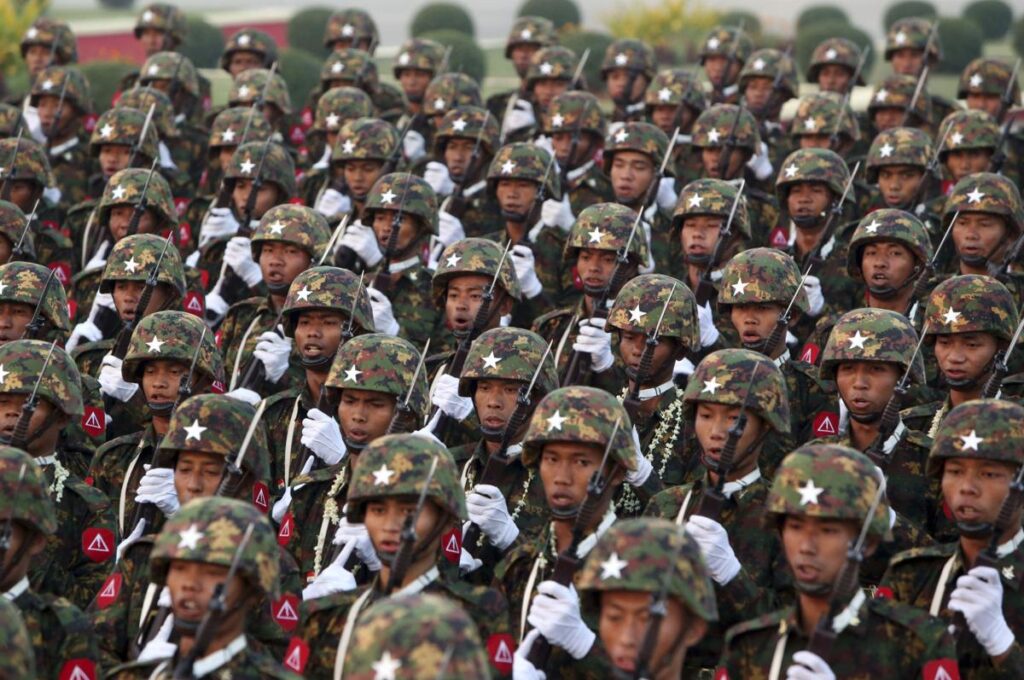

Bangkok, Aug 5 (AP/UNB) — A United Nations fact-finding mission called Monday for an embargo on arms sales to Myanmar and targeted sanctions against businesses with connections to the military after finding they are helping fund human rights abuses.

The mission released a report detailing how businesses run by Myanmar’s army, also known as the Tatmadaw, are engaged in such violations and provide financial support for military operations such as efforts to force Muslim Rohingya out of Rakhine state.

The report focused mainly on the activities of two main military-dominated conglomerates — Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd. and Myanmar Economic Corp. It said nearly 60 foreign companies have dealings with the at least 120 businesses controlled by the two companies in industries ranging from jade and ruby mining to tourism and pharmaceuticals.

“The revenue that these military businesses generate strengthens the Tatmadaw’s autonomy from elected civilian oversight and provides financial support for the Tatmadaw’s operations with their wide array of international human rights and humanitarian law abuses,” Marzuki Darusman, the Indonesian human rights lawyer who chairs the fact-finding mission, said in a statement.

The fact-finding mission, empowered by the U.N.’s Human Rights Council, was established in the wake of a brutal counterinsurgency campaign begun in 2017 that drove more than 700,000 members of the Rohingya minority into neighboring Bangladesh.

A wide array of international groups have shown killings, rapes and the torching of villages carried out on a large scale by Myanmar security forces. Myanmar’s government has denied abuses and said its actions were justified in response to attacks by Rohingya insurgents.

The mission, which investigated human rights violations against ethnic groups in other parts of the country as well, also documented the abuses in an initial report issued last year.

Military leaders in charge of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd. and Myanmar Economic Corp. are among officials the fact-finding mission earlier said should be investigated for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

Monday’s report urged the U.N. and member governments to immediately impose targeted sanctions against companies run by the military and encourages carrying out business with firms unaffiliated with the military instead.

The U.S. lifted long-standing economic sanctions against Myanmar in 2016. But it has reimposed some sanctions against members of the military, citing the army’s treatment of the Rohingya.

Myanmar’s Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing is already being sanctioned by the U.S. for the Rohingya campaign. In July, Washington. barred him, his deputy Soe Win, and two subordinates believed responsible for extrajudicial killings from traveling to the U.S.

Myanmar’s military objected to the sanctions, saying they were a blow against the country’s entire military and that the U.S. should respect investigations into the Rakhine situation being conducted by the army.

The U.S. sanctions against top commander are useful and have a cumulative effect, Christopher Sidoti, an international human rights lawyer and former Australian Human Rights Commissioner, told The Associated Press.

At the same time, he said they are small and symbolic — “only a start” — and more actions such as freezing their bank accounts are needed.

In the past decade, as Myanmar transitioned from a military regime to a civilian government dominated by the military, businesses have poured investment into one of the region’s fastest growing economies. The country of more than 60 million people long was isolated and has huge potential, but the crisis over the treatment of Rohingya and other ethnic minorities has raised the risks for investors.

The report issued Monday alleged that at least 15 foreign companies have joint ventures with military-affiliated businesses.

The report did not suggest the foreign companies have directly violated any laws. But it said such ties pose “a high risk of contributing to or being linked to, violations of human rights law and international humanitarian law. At a minimum, these foreign companies are contributing to supporting the Tatmadaw’s financial capacity.”

It points to South Korea’s Inno Group, which is building a “skyscraper city” in Yangon in a joint venture with MEHL. Posco Steel Co. also has joint ventures with military related companies, as does Pan-Pacific, an apparel maker that according to its website began operating in Myanmar in 1991 and is a supplier of shirts and other garments to many fashion brand names.

Some foreign investors in Myanmar have conducted human rights assessments in response to criticism over their activities in the country, including Japan’s Kirin Holdings Co. Ltd., which has taken stakes in Myanmar Brewery Ltd. and Mandalay Brewery Ltd.

But dozens of companies conduct business with Myanmar partners that have ties to the two big military-linked conglomerates, the report said. Others rent office space from them or operate in industrial zones that are owned by MEHL.

The report also raised concerns over suppliers of arms to the Myanmar military. They include China, Russia and North Korea, but also India, Israel and Ukraine, it said.

The report outlined links between the military and its businesses and jade and ruby mining in northern Myanmar, where the army has been fighting ethnic insurgencies for decades.

The fact-finding mission did not propose sweeping sanctions against Myanmar.

“Removing the Tatmadaw from Myanmar’s economy entails two parallel approaches. In addition to isolating the Tatmadaw financially, we have to promote economic ties with non-Tatmadaw companies and businesses in Myanmar,” Darusman said. “This will foster the continued liberalization and growth of Myanmar’s economy, including its natural resource sector, but in a manner that contributes to accountability, equity and transparency for its population.”